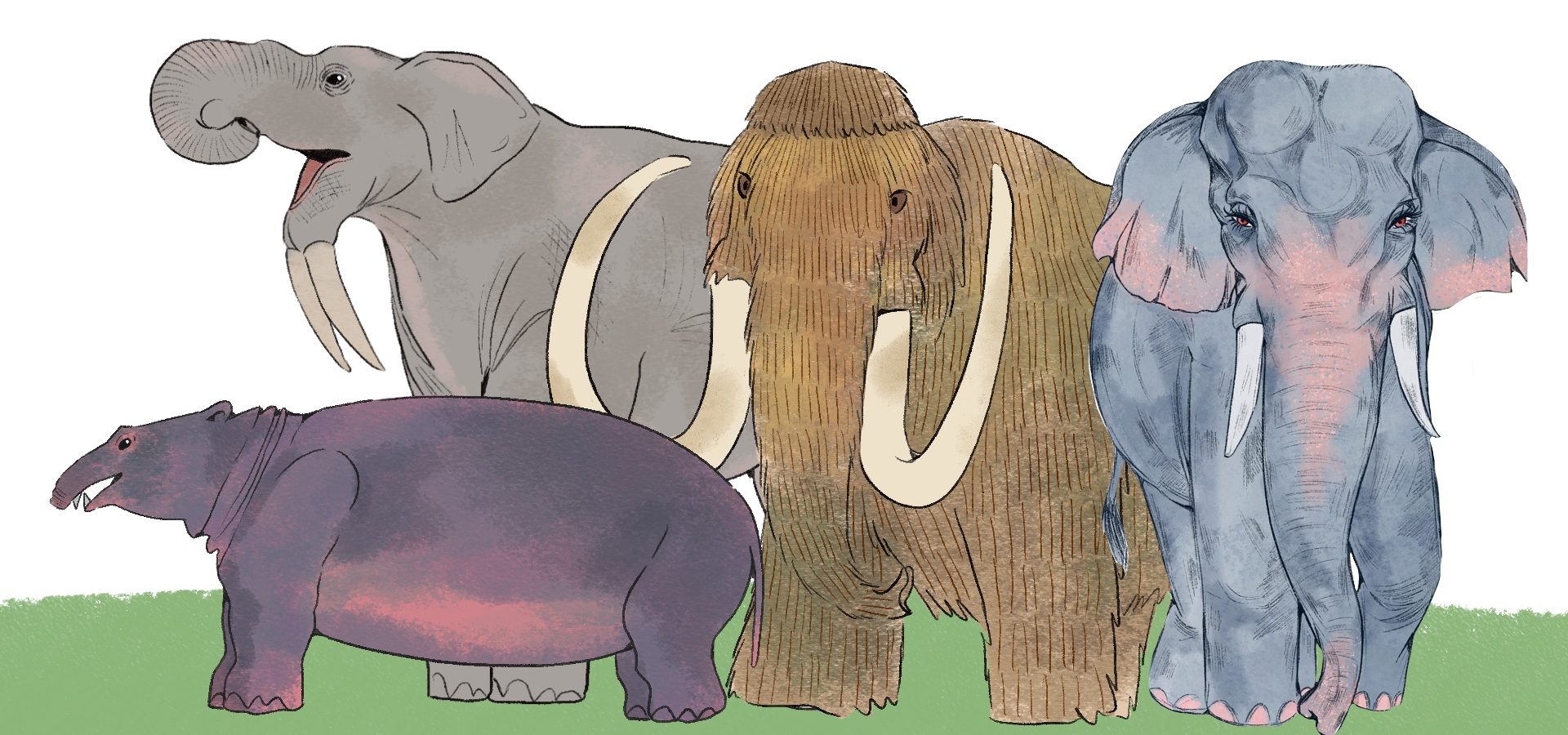

Today there are three living elephant species found on Earth: the Asian elephant, the African forest elephant and the African savanna elephant. These elephants are the descendants of mammals that lived millions of years ago and represent the last remnants of the order Proboscidea. The fossils of their ancestors are still being unearthed to this day, and many have been identified using incomplete fragments of their bones. Understanding the relationship between extinct species and their living relatives is a difficult task, but each discovery along with advancements in paleobiology brings us closer to a very different ecosystem that is lost to us now.

Palaeobiology

So what exactly is Paleobiology, and how does it help us get to know the ancestors of elephants? Let’s begin with palaeontology: Palaeontology is the study of animal and plant fossils. Paleobiology is a branch of palaeontology that is about the biology of fossil organisms. Paleobiology combines the methods and findings of natural sciences (a branch of science that deals with the physical world) with that of earth science palaeontology (study of life on Earth using fossils). It helps us answer questions about the history of life using fossils that are millions of years old, and applying current knowledge of organisms to understand it. For example, the preserved remains of woolly mammoths Dima, Lyuba and Yuka that were discovered by Siberian locals were turned over to scientists for a deeper understanding of this extinct mammal. While Yuka is one of the best preserved specimens of the woolly mammoth to ever be found (allowing researchers to even draw flowing blood from her body), most fossils aren’t found in such good condition. Hence paleobiologists have to study long durations of evolution to derive conclusions from just a few pieces of bones that can be recovered.

![Wooly Mammoth [Photo (c) Wildlife SOS/Malavika Jayachandran]](https://wildlifesos.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Wooly_Mammoth.jpg)

Proboscidea

The term “Proboscidea” was coined by Carl D. Illiger in 1811 to encompass both living and extinct elephants, including their relatives, within a taxonomic order. This classification was based on the defining feature of this order: the proboscis, or trunk, which is a remarkable combination of the nose and upper lip. It could perform the functions of breathing, olfaction, touch, manipulation and sound production.

The trunk of an Asian elephant that we see today is a marvel of considerable evolution, with approximately 1,50,000 muscles. It can perform fine motor skills like delicately picking up small items like peanuts as well as gross motor skills like breaking off thick branches of a tree.

One of the early proboscideans that is speculated to be the ancestor of our extant elephant species is the Moeritherium which was a small, semi-aquatic hippo-like mammal that lived about 37-35 million years ago. Though researchers think that it did not have a trunk, they speculate that it had a long upper lip (Freeman, 1981).

![Moeritherium [Photo (c) Wildlife SOS/Malavika Jayachandran]](https://wildlifesos.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Moeritherium.jpg)

In the geologic period of Oligocene, another mammal called the Palaeomastodon (a descendent of Moeritherium) lived in the marshes and savannahs of what is now Egypt, Ethiopia, Libya, and Saudi Arabia. These mammals possessed tusks both in their upper and lower jaws.

Many basic proboscideans have existed throughout history, including the Deinotherium that had tusks in their lower jaw pointing downwards, the Gomphotherium that had two sets of tusks in their upper jaw and lower jaw, and the woolly mammoths that were hunted by humans for their meat and ivory. So far, about 175 species and subspecies of proboscidea are known to have existed and are classified into 42 genera and 10 families (Shoshani & Tassy, 2005).

![Deinotherium [Photo (c) Wildlife SOS/Malavika Jayachandran]](https://wildlifesos.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Deinotherium.jpg)

What we now call the northern coast of Africa is where the earliest proboscideans were discovered, and is speculated to have served as a potential centre from where it branched out. Initially, proboscideans were limited to the Afro-Arabia region, but during the late Oligocene and early Miocene periods, there was a notable movement out of these regions. Many of them seem to have moved through Africa into Europe and Asia (Shoshani, 1998).

In terms of dietary preferences, early proboscideans mainly exhibited browsing behaviour, while grazing became the trend in later periods. Grazing and browsing are two feeding strategies observed in herbivores and are distinguished by the different types of vegetation they consume. Browsers primarily feed on leaves, fruits of tall woody plants, shoots, and shrubs while grazers eat grass and other vegetation found in close proximity to the ground.

The upper and lower incisors of these proboscideans underwent changes to adapt to their needs at the time. For example, the Platybelodon (also known as ‘shovel-tuskers’) had flat tusks which were probably used to scoop vegetation. The elephants of today have a very unique and complex dentistry with their teeth placed horizontally (like a conveyor belt) instead of vertically, like in humans. New sets of molars develop at different stages in their lives to prevent all their teeth from wearing down due to the amount of chewing and grinding that they indulge in every day.

It is speculated that many proboscideans from the post-Miocene era share another similarity with modern elephants: the musth gland. This gland was positioned on the side of their face, with an opening located between the eye and ear. By examining the shape and size of their skulls, it was deduced that this gland probably existed in many other extinct proboscideans as well. Its primary purpose was to convey social dominance, and during periods of increased sexual activities, the gland would enlarge and release chemical substances.

Overall, the proboscideans underwent some common changes as time passed. These changes included:

- Increase in size

- Elongation of limbs

- Expansion of the skull

- Reduction in the length of the neck

- Formation of a trunk (proboscis)

- Formation of tusks

The current surviving members of proboscidea — Loxodonta and Elephas — both emerged in Africa. While Loxodonta stayed in the continent, Elephas dispersed, leading to very different subpopulations. Asian and African elephants have many distinctions between them, but fairly recently, African populations were also distinguished into two different subspecies.

![Asian and African elephant [Photo (c) Wildlife SOS/Teesta Mukherjee]](https://wildlifesos.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/asian_and_african_elephant_difference_teesta_illustration.jpg)

Despite there being over 175 species in the order proboscidea that once walked over the entire world, there are only three species that are alive today. While it would be an oversimplification to point out any one factor in their decline, it can be noted that climate change, adaptability to local changes and competition for limited space and resources are some of the causes of their extinction. Many of these extinctions may have been a result of natural selection and the world running its course, but the decline in the number of our present-day elephants most definitely has to do with human interference and encroachment.

The elephants of today are a keystone species that are constantly battling against shrinking habitats and human-wildlife conflict. At Wildlife SOS, our team is working to provide aid to Asian elephants that have been rescued from exploitative conditions. You can support us by staying informed on the latest updates about wildlife conservation, and raising your voice for the last remaining members of the proboscidean order.

To follow our efforts towards wildlife conservation, subscribe to our newsletter.

REFERENCES:

Freeman, D. (1981). Elephants, the Vanishing Giants. Putnam Publishing Group.

Shoshani, J. (1998). Understanding proboscidean evolution: a formidable task. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 13(12), 480–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01491-8

Shoshani, J., & Tassy, P. (2005). Advances in proboscidean taxonomy & classification, anatomy

& physiology, and ecology & behavior. Quaternary International, 126–128, 5–20.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2004.04.011