Reptiles & Others

India is home to a variety of snake species ranging from extremely venomous snakes like the Cobra and Common krait and in some rare cases, Saw scaled viper & Russell’s viper, to relatively harmless and non-venomous ones like the Common sand boa, Red sand boa, Wolf snake, Rat snake and Black-headed royal snake. Largely misrepresented and often perceived as dangerous, reptiles are met with fear and hostility, leading to incidents of human conflict with this species.

Wildlife SOS works to alleviate these misconceptions and sensitize people to these incredible animals, using education, awareness and positive intervention to help mitigate human reptile conflict.

The Wildlife SOS 24×7 Rapid Response Unit works round the clock attending to distress calls from members of the public, police, animal lovers and other organizations about wild animals in peril or caught in conflict situations.

Rapid urbanisation and habitat modification has redefined the lines between cities and forests. Consequently, wildlife living in proximity to such expanding areas struggle to find a foothold their decreasing habitat, and have to adapt in order to survive in urban habitats.

SPECTACLED COBRA

The Spectacled cobra, or the Indian Cobra, is a highly venomous snake found predominantly found in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bhutan. Indian Cobras have a long string of baseless beliefs attached to their existence leading to escalating incidents of conflict with humans. A major part of the superstition stems from snake charmers who use cruel methods such as sewing and taping the mouth of the snake, or by breaking their fangs in order to render them “safe” or “harmless”. With no proper nutrition and being forcefully fed milk which the snakes are unable to digest, Wildlife SOS Rescue teams rescue snakes from deplorable conditions where most of them do not even make it through. Over the years, our teams have rescued cobras from the most unlikely places such as VIP offices, Metro stations, toilets, car seats, beds and mattresses etc.

CIVET CAT

Found predominantly in the tropical areas of Asia and Africa, civets are small cat-like animals that are active mainly during the night, when they come out of their burrows to forage. They can survive in a wide range of habitats and can be seen in urban environments, but quite rarely, as they tend to be shy and wary of humans.

Wildlife SOS frequently crosses paths with two common subspecies— Asian Palm civet and Small Indian Civet as more often than not, they find themselves in distress situations. Our Rapid Response Units have rescued civets that had fallen victim to road accidents, found trapped in water tanks as well as from people’s homes, airports and even libraries! The civet species is presently under threat from habitat encroachment; human-conflict situations and poaching as the glandular secretion of civets are popular for creating musks and perfumes.

MONITOR LIZARD

The Bengal monitor (Varanus bengalensis) or common Indian monitor is one of the four monitor lizards found in India. Growing nearly 5ft in length, these solitary reptiles spend most of the day in constant movement, where they sometimes stray into urban settlements in search of food and water. The Wildlife SOS Rapid Response Unit frequently respond to calls about monitor lizards that wander into peoples homes and end up behind the refrigerator or air conditioner, in a classroom or even inside the toilet!

Contrary to popular belief, these lizards are non-venomous and non-poisonous but are sometimes killed when in conflict with humans. Though mostly non-offensive , they can bite or even use their strong claws in retaliation if threatened or provoked. Folklore and belief has it that their genitalia can be used in rituals or medicine, but such claims have no scientific truth.

Monitor lizards, which also help control insect and rodent populations, are protected under Wildlife Protection Act of India 1972 and an international treaty that bans illegal wildlife trade. However, the lizards are poached for their meat and skin—used to make craft drums and sandals which is the greatest threat to their decreasing population. Additionally, dried genitals of monitor lizards are often passed off as the rare hatha jodi plant. The plant is believed to bring good luck to its bearers and also used in occult practises.

BLACK-HEADED ROYAL SNAKE

The black-headed royal snake is a non-venomous species and they mostly feed on rodents, lizards, birds and small mammals. They are excellent climbers and are found on trees, low bushes and crevices. As a defence mechanism under threats and stressful situations, they coil up and hiss loudly but rarely bite in retaliation. Juveniles have pale brown patches and lack the distinct irregular black markings that adult royal snakes have on their body.

Royal snakes do not pose any threat to humans and can be easily identified by the distinct black colouring on their head, and the dark speckles on their bodies. People unnecessarily panic on spotting a snake as not everyone can distinguish the venomous ones from non-venomous. The Wildlife SOS team works hard to sensitize people to these largely misunderstood creatures and make it possible for them to co-exist in urban areas.

Habitat fragmentation causes these reptiles to stray into and adapt to an urban environment due to easy access to prey and shelter. The Wildlife SOS Rapid Response Unit rescues hundreds of such snakes each year, sometimes from the most unexpected places like the premises of the Prime Minister’s house or the State Legislative Assembly!

INDIAN ROCK PYTHON

The Indian rock python is a large non-venomous python species that can length out to as long as 20-ft! They are native to tropical and subtropical regions of the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. This particular species is under the ever increasing threat of habitat loss, poaching and is a sought after species in the illegal pet trade.

The Indian rock python is protected under Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 and listed under Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES), which regulates the international trade of wildlife species.

Although non-venomous, a python’s bite can be injurious, so one has to be careful while carrying out such rescue operations. They are often confused with the venomous Russell’s viper and these reptiles often get killed when they venture into human habitations. Wildlife SOS works towards changing this attitude and sensitizing the public to the presence of urban wildlife.

INDIAN RAT SNAKE

The Indian Rat Snake also known as the Oriental rat snake are a highly adaptable species and are commonly found in various parts of Southeast Asia. They often wander into human habitation due to depletion of natural prey base. However, due to their resemblance to cobras, this species is often misidentified as the highly venomous snake and is met with hostility and fear.

Rat snakes are non-venomous and non-aggressive but can bite if provoked or threatened, out of self-defence. Wildlife SOS receives rescue calls for rat snakes commonly found in storage rooms of houses as well as in gardens or even bathrooms! Rat snakes also fall victim to snake charmers who often sew their mouths shut and at a result, they are unable to eat and slowly starve to death.

BARN OWL

The Barn Owl (Tyto alba) is a widely distributed owl species and commonly found in the Indian subcontinent. They prey primarily on rodents and other small mammals and occasionally even small birds. Barn Owls make their nests in unused burrows, tree cavities, terraces and wells away from human habitation, so that they are not disturbed. They are a nocturnal species that are very shy and wary of humans. Owls are considered to be friends of farmers as they keep a check on the rodent population.

The superstitions regarding owls in India are great and never ending. They have always been associated with demon rituals, spooky tales and folklore. Driven by religious myths and superstitious beliefs, owls are poached for their body parts such as talons, skulls, bones, feathers, meat and blood, which are then used in talismans, black magic, traditional medicines etc. Every year, countless owls face a cruel fate at the hands of poachers who are catering to ignorance and misguided beliefs.

Besides facing a massive threat from poachers and wildlife traffickers, owls are also at risk from kite manjas (glass-coated threads) that more often than not cause strangulation and severe wing injuries. Every year, the Wildlife SOS rescue helpline receives numerous calls about owls caught in such perilous situations.

In India owls are protected under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 and the International trade in owls is prohibited under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES).

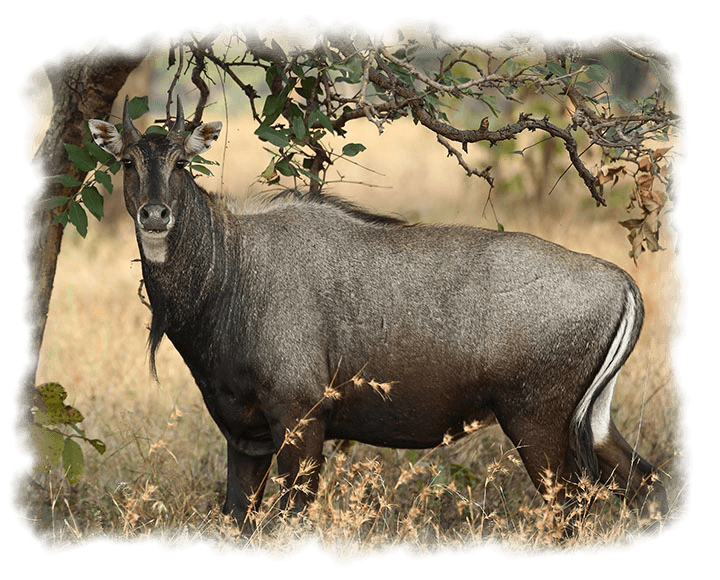

NILGAI

The Blue bull or Nilgai is a species of antelope that is endemic to India and is considered the largest Asian antelope. The adult male has a bluish-grey hue which is what gives them their unique name, while the adult female is mainly light brown in colour.

The nilgai is listed “least concern” in IUCN Red List, but however is a victim of a range of man-animal conflict as well as road accidents. Owing to rapid urbanisation, their natural habitat becomes threatened and they venture out to forage which often leads them to a speeding highway that becomes the reason of brutal highway accidents.

They are also poached for trophy-hunting and their meat is considered a delicacy in some parts of the country. Time and again, Wildlife SOS receives calls about nilgais that are injured, caught in conflict situations or have fallen victim to road accidents.

BLACK KITES

The black kite (Milvus migrans) is a medium-sized bird of prey. It is thought to be the world’s most abundant species of Accipitridae, although some populations have experienced dramatic declines or fluctuations due to habitat destruction, loss of prey base and poisoning from agricultural pesticides. Black kites are opportunistic hunters and are more likely to scavenge. They spend a lot of time soaring and gliding in thermals in search of food. Their angled wing and distinctive forked tail make them easy to identify. They have a distinctive shrill whistling sound followed by a rapid whinnying call.

Black Kites often perch on electric wires and are frequent victims of electrocution. Their habit of swooping to pick up dead rodents or other roadkill leads to collisions with vehicles. Raptors such as kites generally fly at higher altitudes and are more prone to suffering under the scorching sun. While descending down in search of prey or water, they collapse on the ground due to dehydration, heat exhaustion and lack of shade. During the sweltering summer months, our Rapid Response unit received maximum number of calls about kites that have collapsed due to heat strokes and dehydration.

COMMON KRAIT

The Common Krait can be found across most of India’s mainland and is one of the four most venomous snake species in the country. It is nocturnal so most of its movement is limited to night time. During the day, it is often found resting in crevices, rodent burrows, termite mounds or under rocks. They are cannibalistic in nature and also prey on other snakes besides feeding on rodents, frogs, toads and lizards.

While seeking out shelter in cooler places or easily available prey, kraits often find their way into houses, leading to conflict with humans.

Snakes are often demonized due to the suspicion they are often surrounded with, but in reality, a snake never strikes unless it’s forced to defend itself. Nonetheless, it is extremely important to take certain precautions while dealing with snakes, especially those that are venomous. Sometimes these rescues can be dangerous and risky, but our team is trained to handle and carry out such sensitive operations, in the interest of public safety and protection of urban wildlife.

PAINTED STORK

The painted stork is a large wader in the stork family and is found in the wetlands of the plains of tropical Asia south of the Himalayas in the Indian Subcontinent and extending into Southeast Asia. Their distinctive pink tertial feathers as well as yellowish-orange mask around the mouth with pinkish legs is what gives them this unique name.

The Painted Stork is a near-threatened species as human-induced factors such as water pollution, dumping of untreated chemical wastes etc. have led to the decline in their natural habitats and furthered their invasion. Wildlife SOS receives calls for painted storks that get injured during the kite-flying festival celebrated in India wherein the glass-coated thread ends up seriously injuring and killing many birds, of which painted stork is one. Careful medical examination and treatment rendered to these birds makes them fit to be released back into the wild!

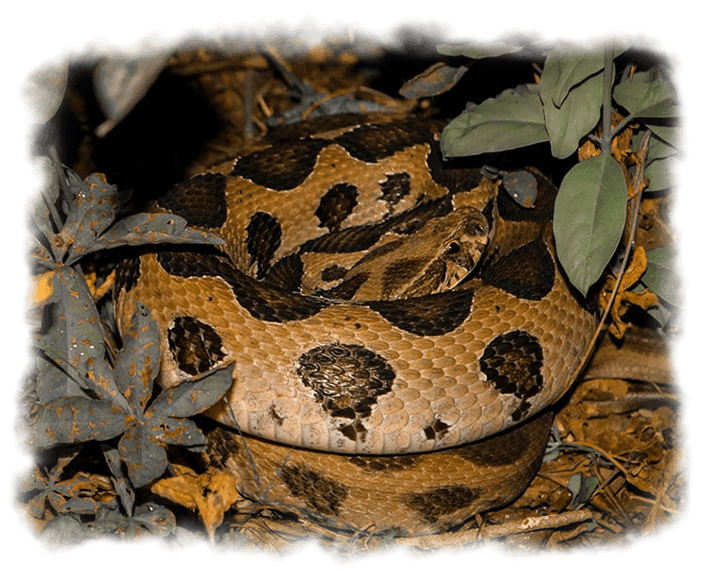

RUSSELL'S VIPER

Russell’s viper is one of the ‘big four’ venomous snake species found in Asia throughout the Indian subcontinent, much of Southeast Asia, southern China and Taiwan. Perhaps the most quickly acting venom, people who suffer from snakebite from a Viper snake almost instantly experience a wide range of blood incoaguibility and kidney failure along with dizzy spells. They commonly come in contact with humans as they are found in open grassy areas, scrub jungles and rocky hillocks.

When threatened, they form a series of S-loops, raise the first third of the body, and produce a hiss that is supposedly louder than that of any other snake. Panicked calls about Russell’s viper sightings mainly come from people’s houses or backyards but such sightings are quite rare as these snakes are shy and elusive by nature.

Having had years of experience on their side, the team handles such rescues with extreme caution, as the fangs of a Russell’s viper are the largest in length among Indian snakes and they react violently to being picked up, and also can bite with a snap.

CHECKERED KEELBACK

Checkered Keelback (Xenochrophis piscator) also known as the Asiatic water snake is a non-venomous snake species, endemic to Asia and Southeast Asia. This snake is characterized by great diversity in coloration and is found predominantly in water-bodies such as lakes, rivers and ponds as well as drains, agricultural lands, wells etc. They are protected under Schedule II of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972.

Though non-venomous, keelbacks turn aggressive when threatened, and may bite in retaliation or self-defence. Owing to its offensive nature, they are also often confused with cobras and are met with hostility. Principal threats to this species involve loss of habitat, water pollution and dumping of industrial effluents in water bodies, conflict situations and road mortality, especially during the monsoon season. Monsoons mark the mating season for frogs and being a common prey base for snakes, a rise in their population attracts various snakes in the city that depend on them for survival.

VULTURES

In South Asia, a number of vulture species, suffered a major decline in their population, leaving them at the risk of extinction. The reason for the decimation of their numbers was an anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac, commonly used in cattle. Vultures feeding on cattle ingested the drug, which caused fatal damage to the birds’ kidney and liver. A ban on diclofenac in India in 2006 spelt hope for the struggling species and populations in the region have recovered considerably since the ban.

Rescue calls pertaining to vultures mainly come when they are found injured due to kite manjas (glass-coated thread) telephone lines or victims of electrocution. During summers, we attend to several cases of vultures suffering from heat exhaustion as they then to fly at higher altitudes, hence more susceptible to heat strokes and dehydration. Vultures play an important role in the ecosystem as by feeding on carrion, they are disposing off the carcasses of dead animals that would otherwise be a breeding ground for infectious diseases.

GOLDEN JACKAL

Belonging to the canine family and closely related to wolves and dogs, jackals are medium-sized animals found in the wild and native to Southeast Asia, South Asia and Southwestern Europe. Jackals play an important ecological role and are valuable for the health of a habitat. Omnivores in nature, they feed on small mammals, insects, hares, fish, birds and fruits and often venture into human habitats in search of the same.

They are increasingly becoming victims of man-animal conflict owing to rapid urbanisation that leads to decreased forest covers and the animals venturing out to urban settings to search for food. The Golden jackal or Indian jackal is protected under Schedule II of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972.

Many a times, jackals cross high-speed highways and expressways and become victims of brutal road accidents that cause gravely injuries or even death. Wildlife SOS also attends to rescue calls about jackals trapped in wells, caught in conflict situations or those that have been displaced from their forested homes.

STRIPED HYENA

The Striped Hyena is a species of hyena native to North and East Africa, the Middle East, the Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent. They are generally smaller in size compared to their African counterparts, and can be characterised by their pointed ears and a broad forehead. They are listed as “Near Threatened’ by IUCN Red List.

India is home to 20% of the Hyena population in the world but their numbers are steadily declining. Some major threats to hyenas in India are human-wildlife conflict situations, road accidents and poacher’s snares. Increasing anthropogenic pressure on their habitat and food sources has driven the animals closer to human settlements in search of food. Hyenas are opportunistic carnivores who prefer eating carrion but also feed on easily available prey such as livestock and poultry.

Wildlife SOS has rescued many hyenas that were caught in deadly poaching devices or victims of conflict situations, wherein many a times, they are rendered so badly injured that their survival chances are miniscule.

BLACK BUCK

The Black buck (Antilope cervicapra) is an antelope species that is native to the Indian Subcontinent. This species is protected under Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 and is thereby granted the same level of protection as the tiger and elephant. During the 20th Century, the Black Buck population in India drastically declined due to excessive hunting, deforestation and habitat degradation.

The males can be easily identified by their characteristic twisted horns and darker coloured marking on the face and body. Habitat loss and modification, extensive poaching and illegal wildlife trade are some of the major threats to native population of this magnificent antelope.

These mammals mostly inhabit India and areas of Pakistan, and are generally found near grasslands, semi-deserts and deciduous forests. They are mostly social creatures, living in herds consisting of anywhere between 5 to 50 individuals. They are herbivores and eat fruits, flowers, shrubs, bushes and grasses.

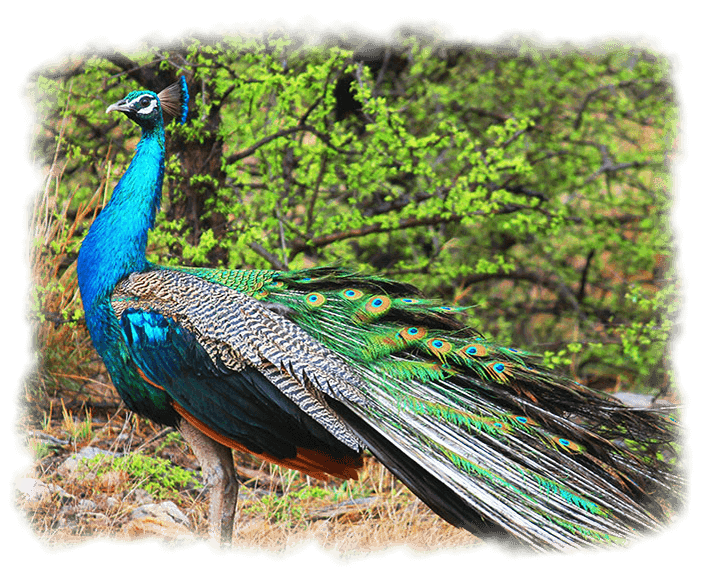

Indian Peafowl

The Indian Peafowl, also known as the common Peacock, are large, colourful pheasants known for their iridescent tails and are native to the Indian Subcontinent. Peacocks are also the National Bird of India and are protected under Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972.

They are not uncommon in residential areas near forested regions and green belts within the national capital. It is easy to sight them foraging for food during the early hours of the morning. The most common reason for distress calls that the Wildlife SOS Rapid Response Unit receives for the bird is when it is found weak or with no mobility due to severe dehydration in the summer.

Adult peacocks shed their tail feathers at the end of each breeding season and according to the Indian law, the trade in these naturally shed tail feathers is a notable exception. However, there are reports from some parts of the country of poachers poisoning the birds for the purpose of plucking the feathers. Enforcement against this illegal trade is challenging as the only means of distinguishing naturally shed feathers from the plucked ones is by examining the base which the poachers overcome by trimming the bottom part.

Langur

The Gray Langur, sometimes referred to as the Hanuman langur after the monkey-god Hanuman, is native to the Indian subcontinent and can adapt to various habitats.

According to The Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 and under the Indian Penal Code, the langur is a protected species under Schedule II which means langurs cannot be owned, traded, bought, sold or hired out. However, these primates are being poached from the wild into illegal captivity where their owner trains them to “entertain” the public to earn daily wages. Moreover, their large incisors, shrill screams and fearsome reputation makes them a popular choice to unethically ward off rhesus macaques. They are kept in gruesome conditions which significantly reduces their chances of survival.

The Wildlife SOS Anti-poaching unit assists the State Forest department in seizing illegally held monkeys and if possible, releases them back into their natural habitat.

The species is also suffering due to habitat degradation due to which they are forced to enter human habitation in search for food, making them vulnerable and leads to human-primate conflict. People also feed monkeys for religious sentiments which conditions them to associate human presence with food and complicates the matter further.

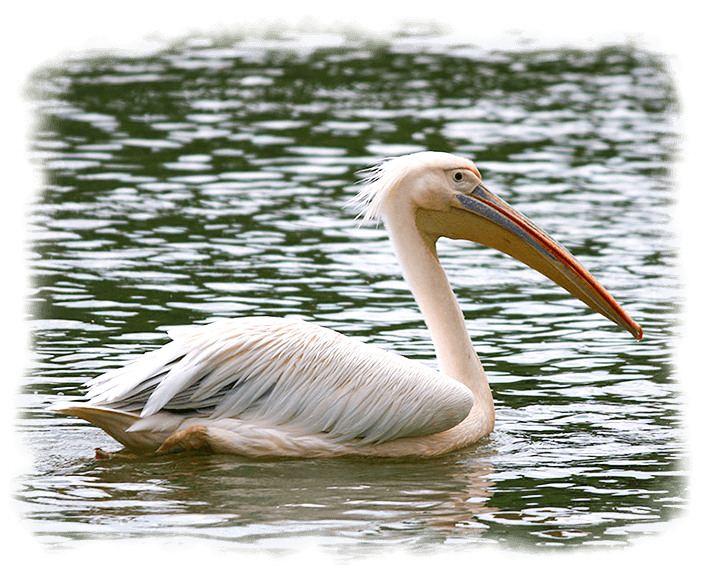

Great White Pelican

The Great White Pelican (Pelecanus onocrotalus) also known as the Rosy pelican belongs to the family Pelecanidae. They are some of the heaviest flying birds and have an astounding wingspan that can range from 7.4 foot to 12 foot. Their diet mainly consists of fish, while also feeding on small birds, frogs and crustaceans.

Pelicans are prevalent across freshwater wetlands, marshes and deltas of the sub-continent, anywhere there is enough grass and reed beds for nesting. It travels long distances for migration, and lives, feeds and roosts in large colonies.

Although classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List, they are exploited for various reasons. Habitat destruction is a major threat to the species as caused by rapid urbanisation, deforestation and agricultural expansion. Flooding of their habitats is also a reason for their population’s decline, as is pollution and disease. Once disturbed, the whole colony leaves and does not return to the same nesting grounds.

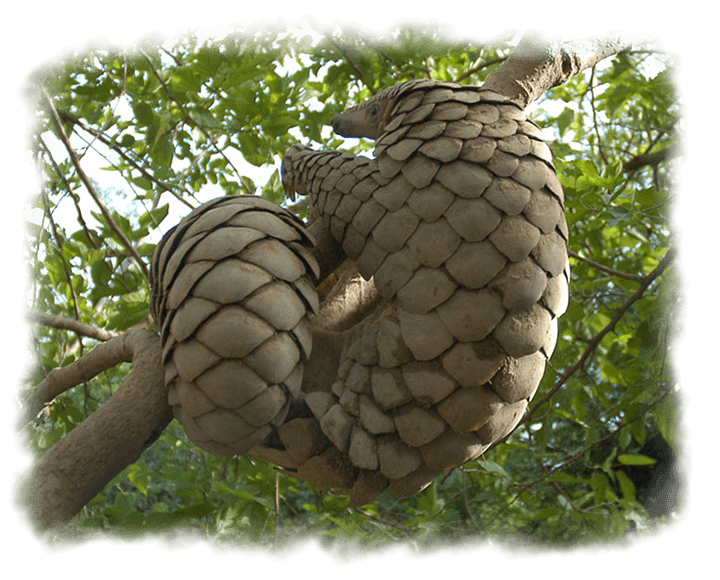

PANGOLIN

Presently the world’s most illegally trafficked animal, the pangolin species are in grave danger as thousands are being brutally hunted down for their scales, meat and for the baseless belief of use in traditional Chinese medicines. The Indian Pangolin as well as the Chinese Pangolin are both protected under Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 and the Indian Pangolin lists as “Endangered” and the Chinese Pangolin is now listed as “Critically endangered” by the IUCN Red List.

These scaly ant-eaters are extremely important to the forest ecosystem as their long tongues and defined claws are helpful in digging holes to eat up the ants which in turn helps in keeping the rodent population in check. The increasing poaching comes from lack of awareness in conservation of pangolins, which is why Wildlife SOS takes pride in being at the forefront of educating people and spreading awareness on the present situation of the pangolins and how the world needs to work as one in order to make this a better place for animals in the wild.

COMMON WOLF SNAKE

The Common Wolf snake, also known as the Oriental Wolf Snake, is a nonvenomous snake widespread throughout India. Commonly found in urban areas, the snake is highly adaptive. Its name comes from two large teeth in both jaws, giving it a canine-like appearance. Its snout is almost square-like, allowing it to dig in soft sand grounds. They are relatively small and slender snakes, growing up to approximately 3 feet.

These nocturnal reptiles rest during the day in dry and secure places like rocks and crevices near houses. They are most active at night looking for prey like rodents and lizards (geckos and skinks.) Habitat fragmentation often forces these snakes to venture into human settlements. They are great climbers and can even climb building walls!

The snake is commonly mistaken as the highly venomous Common Krait. This is not a mere coincidence but a part of “evolution mimicry” that allows the snake to survive! The common wolf snake even has similar behaviors to that of the Krait – as a defense mechanism, both snakes conceal their heads under their bodies when threatened. Owing to such similarities with a venomous snake, the wolf snake often is met with hostility and fear.

The wolf snake is a harmless snake who tries to escape if confronted but, if threatened, the snake can repeatedly bite out of self-defense. Most wolf snake bites result in minor swelling and bleeding with no serious harm to humans.

Over the years wildlife SOS has rescued numerous wolf snakes from the strangest of places – inside the engine of a car, temples, and even the Rashtrapati Bhavan!

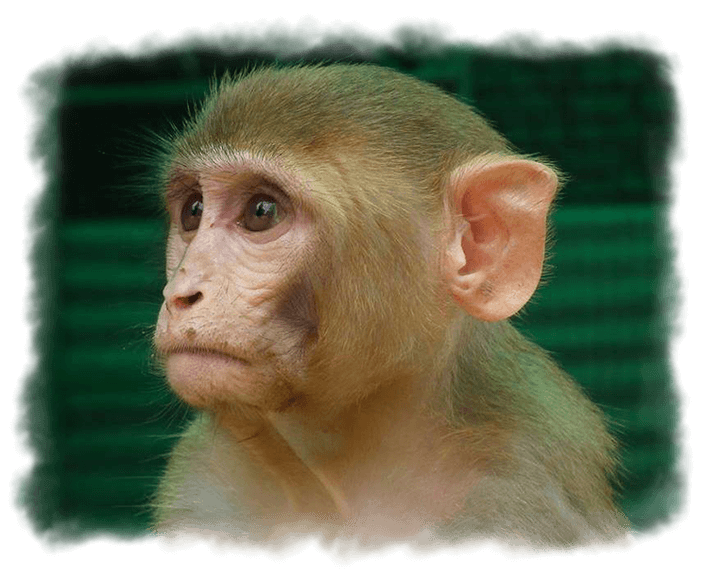

RHESUS MACAQUE

Rhesus Macaque is the most commonly encountered monkey in India. They are found in northern parts of India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Afghanistan, Thailand, Burma, and southern parts of China. They occupy all altitudes and habitats from grasslands to forests to mountains. Their diet mainly consists of fruits, bark, insects, and sometimes even small animals. They are usually found in troops of 18-20, but some troops can even include 200 of them!

The species is classified as Least Threatened in the IUCN red list due to their ability to adapt to a broad range of habitats leading to wide distribution and large population. Some even adapt to densely populated cities in India, where they’ve grown highly dependent on humans for food often breaking into homes!

Human primate conflict, often termed as monkey menace, is on the rise, sadly because of the fragmentation and disappearance of the original habitat that these animals depend on. Today cities generate enough garbage which provides feeding grounds for rhesus macaques. Furthermore, people also feed monkeys for religious sentiments which condition them to associate human presence with food and complicate the matter further. Rhesus macaques are often subjected to stoning, trapping, and shooting as they are considered to be pervasive, destructive pests.

Wildlife SOS has rescued numerous monkeys from human-primate conflict situations, the animal entertainment industry, and from accidents with power lines. Wildlife SOS also rehabilitates and cares for orphaned baby monkeys.

RED SAND BOA

Red Sand Boa, commonly called the Indian Sand Boa, is a non-venomous snake endemic to India, Pakistan, and Iran. Found mostly in dry parts of the regions, it prefers loose soil that breaks easily, creating burrows where it spends most of its time. The Red Sand boa is a nocturnal species that leaves its burrow at night in search of prey. It mostly feeds on mammals like rats, mice, and small rodents.

This species is referred to as “do Muha” in Hindi, translating to “double-headed” due to its thick blunt tail that gives the appearance of two heads. It is also easily recognizable due to its shovel-shaped nose. Its unusual appearance has led to numerous superstitions being attached to the snake. Some consider it to be lucky, while others believe the snake possesses anti-aging properties. Superstition combined with the benign nature of the snake makes it an ideal target for trafficking.

Threatened by illegal trafficking and human-wildlife conflict due to rapid urban expansion, The number of red sand boas are rapidly dwindling. The Red Sand Boa is protected under Schedule IV of Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, making any threat, sale, possession of Sand boa punishable.

Wildlife SOS rescues numerous Sand Boas from snake charmers and wildlife traffickers. Our rescue hotline also receives numerous calls about Red Sand Boas found in the oddest of places – from car seats to the Delhi metro.

Sambar Deer

The Sambar is the largest deer native to the Indian subcontinent, subcontinent, South China and Southeast Asia. They have a thick coat of long, coarse hair which forms a dense mane around the neck, especially in males. The males can be distinguished by their unique stout and rugged antlers, which are typically up to 110 cm long in adult individuals.

Sambars are mostly active during dusk and dawn and though solitary they form small groups during breeding seasons.

They are good swimmers and can easily swim with their bodies fully submerged and only their heads above water. Their senses are highly developed, which is of assistance in detecting predators. When they perceive danger, they make a repetitive honking call.

Sambars are herbivores, eating various grasses, foliage, fruits, leaves, water plants, herbs, buds, berries, bamboo, stems, and bark, as well as a wide range of shrubs and trees. At certain times of the year, they like eating different types of fruit.

Over the years, the Sambar population in the wild has been threatened due to loss of habitat and poaching, making them a Vulnerable species under the IUCN Red Data List. This species is also protected under Schedule III of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972.

Over the years, the Wildlife SOS’s Rapid Response Unit has rescued injured Sambar deers from highways and main roads since they are highly susceptible to road accidents.

Sarus Crane

The Sarus Crane is the tallest flying bird in the world standing up to 152-156 cm tall with a wingspan of 240cm. They are easily distinguished from other crane species by the grey colour plumage and the contrasting red head and upper neck They are found in parts of the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and Australia. This species is under severe threat due to the loss of natural wetlands which form crucial breeding and foraging habitats. They are classified as ‘Vulnerable’ on the IUCN Red List and there is an estimated population of 15,000-20,000 individuals in India.

They are social creatures, found mostly in pairs or small groups of three or four. They mostly breed during heavy rainfalls during the monsoons and are known to mate for life with a single partner. Usually, a clutch only has one or two eggs, which are incubated by both parents for a period of 26 to 35 days. The juveniles follow their parents from the day of birth. The Sarus Cranes construct their nests on the water in natural wetlands or in flooded paddy fields.

The main threat to the Sarus crane in India is habitat loss and degradation due to draining the wetland and conversion of land for agriculture. Wildlife SOS has rescued Sarus Cranes from multiple urban and rural locations, including the Taj Mahal!

Flamingo

The Flamingo is a pink wading bird with thick downturned bills. They have slender legs, long, graceful necks, large wings, and short tails, and range from 90 to 150 cm in height.

Flamingos are highly gregarious birds. Flocks numbering in the hundreds may be seen in long, curving flight formations and in wading groups along the shore. Flamingos are often seen standing on one leg. Various reasons for this habit have been suggested, such as regulation of body temperature, conservation of energy, or merely drying out the legs.

India has two flamingo species – the greater and the lesser flamingos. Most lesser flamingos in India feed in and around Mumbai’s mudflats. The greater flamingos migrate to freshwater and estuarine habitats across Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Delhi, Rajasthan and some other states. Researchers have also had reason to suspect some greater flamingos could even be flying into Mumbai from the Middle East and parts of Africa.

Different species of flamingos have different feeding behaviours. Some species, like the lesser flamingos, use filter-feeding to eat algae and plankton. Other species filter larger prey, like shrimp, molluscs, insects, and larvae. Flamingos live in flocks called colonies to protect individual birds from predators. Parent flamingos produce a red colour crop milk, in their digestive tracts and regurgitate it to feed their young.

On the IUCN Red List, lesser flamingos are listed as ‘near threatened’ and greater flamingos, as being of ‘least concern.’ Wildlife SOS has treated wounded flamingos all over the Delhi NCR area and released them back to the wild.

HEDGEHOG

The Indian hedgehog is native to India and Pakistan. They are nocturnal animals and usually live in burrows in semi-arid or desert regions and are distributed across the states of Gujarat, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. They are insectivorous in nature and absorb moisture from their diet as they do not drink water directly.

Spine covers their dorsal skin and part of the sides and as a defense mechanism they curl up into a ball to protect themselves from predators. Hedgehogs are born with very few spines and within 6-12 hours they started developing the spines, which do not shed unlike that of porcupines.

They feed primarily on insects such as beetles, small vertebrates, scorpions and eggs of ground-nesting birds. In India, hedgehogs are hunted locally for their meat as well as for medicinal purposes on account of various superstitious myths and beliefs attributed to them. They are also kept as exotic pets in most countries.