Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) is a keystone species found in India’s freshwater river ecosystem. Interestingly, the etymology of the species’ common name can be traced to the Hindustani word ghara meaning earthenware pots due to the round protrusion adult males have at the tip of their snouts. This distinctive feature makes gharials the only crocodilian with visible sexual dimorphism. Out of the 26 species of crocodilians in the world, gharials possess the thinnest and most elongated snout, which makes them easily identifiable.

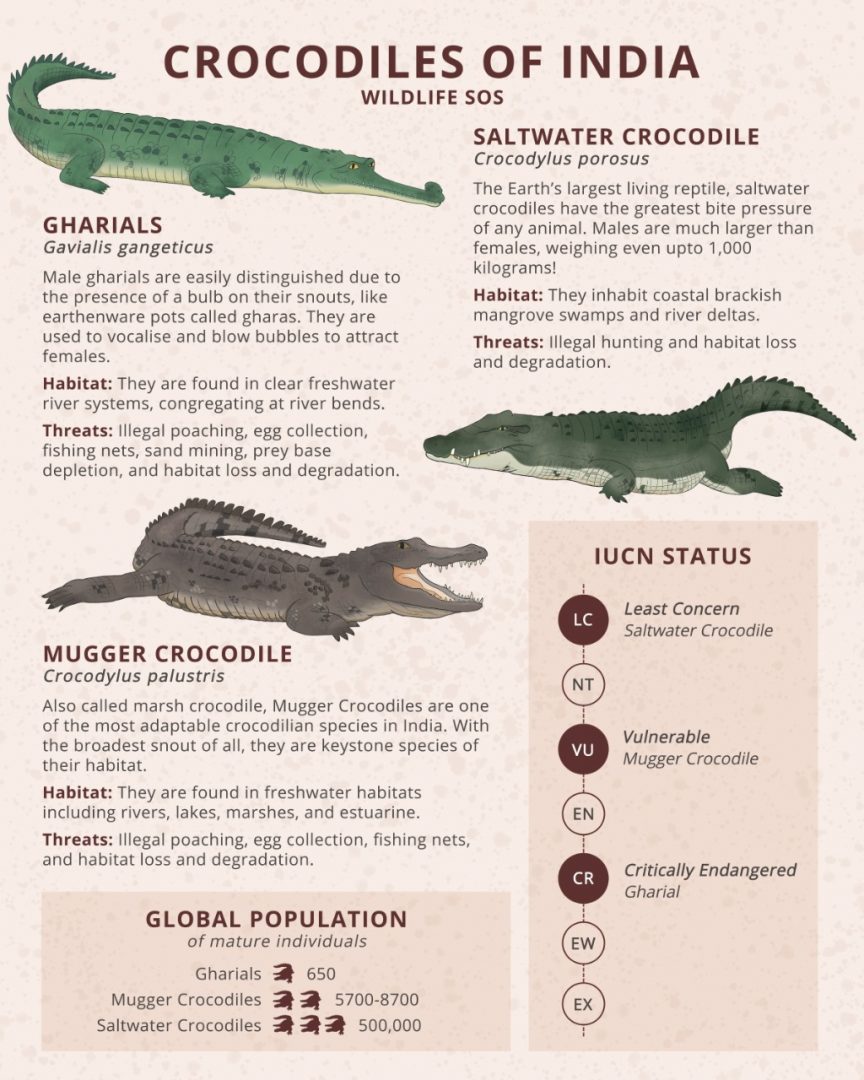

Gharials were once widely abundant in the large river systems spanning five South Asian countries: India, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan. Today, these crocodiles are absent from over 94% of its historical range, leaving approximately 800 mature individuals in the wild that are confined to fragmented tributaries of the Ganga River in India and Nepal. Trophy hunters and traders of gharial skin would target these crocodiles on a large scale, which led to the establishment of a protected area in 1979 around the Chambal River passing India through three states: Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. Given a catastrophic population decline of 98% in under a century, gharials are listed as Critically Endangered in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Being a keystone species of running freshwater, gharials play a major role in the vitality of their ecosystems. A study published in 2022 integrated the function of crocodiles in their environment worldwide with the threat levels each species faces and developed a metric to prioritise conservation efforts. This particular metric, known as EcoDGE (Ecologically Distinct and Globally Endangered), revealed that gharials scored the highest in conservation priority. Gharials were identified as the most functionally distinct species of crocodilians, emphasising that their extinction would leave an irreplaceable void in their environment.

Threats to their survival

Gharials face threats that are as unique as their appearance. They are highly dependent on riverine ecosystems, therefore anthropogenic and environmental pressures affecting freshwater bodies proportionately affect their survival in the wild. Changes in river flow, loss of suitable breeding spots, and undesirable fishing practices gravely impact their ability to repopulate.

Dams and barrages

Gharials have weak leg muscles, which is why they are primarily adapted to aquatic environments and have limited terrestrial capabilities. They only ever leave the water to bask in the sun or nest on sandy banks. Dams and barrages across their range have resulted in fragmented and reduced habitat size. In addition, water abstraction—the removal of water for human use—transforms vast and flowing rivers into unsuitable, non-flowing lakes that lack desirable quality and quantity of water in downstream sections.

In Uttar Pradesh, the construction of the Girijapuri barrage in the Girwa river flowing through the Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary has shrunk the gharial habitat to a meagre 20 km stretch. The loss of breeding habitat and the declining number of juvenile gharials have threatened the population of this species. To understand the disappearance of juveniles from this habitat, a study released in 2023 confirmed that hatchlings disperse downstream when the barrage gates are opened in monsoons due to flooding, leading them to the unprotected area of Ghaghara River, where no conservation efforts to protect gharials are underway. Additionally, as the breeding seasons coincide with the monsoons, the release of water from dams often washes away gharial eggs to areas which do not provide essential conditions for them to reach maturity.

Degraded Nesting Habitats

Gharials favour steep, sandy riverbanks as breeding and nesting habitats. Modification of these habitats due to river flow alterations poses a significant impact on gharial population. Reduction in water flow triggered by natural changes or anthropogenic actions encourages vegetation to grow along riverbanks, restructuring landforms at gharial nesting sites.

The Ghaghara River, which originates in Nepal and is known as the Karnali River there, had undergone a natural channel shift in 2010, reducing seasonal water flow in the Girwa River, where the second-largest wild breeding population of gharials can be found. The redirection of the river water prompted the growth of woody vegetation at riverbanks, which led to a 70% decline in nesting sites.

The above mentioned 2023 study recorded exactly how vegetation prospering along the river affects the incubation of eggs laid by gharials. Their roots can damage the eggshells, while their shoots reduce solar exposure for incubation, which is a primary determinant of the sex of the hatchling. Additionally, vegetation can slow down or block hatchlings’ movement towards water, exposing them to high chances of predation.

Fishing and Sand Mining

The gharial is primarily a fish-eating crocodile inhabiting deep pools that support large fish populations. Supported by uniform sharp teeth and a muscular neck, they are excellent fish catchers. Gharials play a vital role by bringing nutrients from the riverbed to the surface and vice versa, which sustains the fish population and supports the overall health of the aquatic environment.

However, the increased intensity of fishing where gharials reside is a cause for concern as it could deplete the prey base. Fishing nets used also endanger gharials as they often become entangled in them, which reportedly has led them to drown. Their long snouts make them vulnerable to getting caught in the nets, and these gharials are commonly killed or have their toothy snout severed while disentangling them from the nets.

The impact of unauthorised sand mining further disrupts the vital riverine ecosystem that gharials rely on for nesting and breeding. Gharials have lost a significant portion of their nesting habitat along the Chambal and Son rivers, deemed to be protected as sanctuaries, to rampant sand mining.

Additionally, river bank cultivation and gharial egg poaching for consumption are some factors that may lead to the species’ extinction from local areas. Studies show that fragmented gharial populations exist in unprotected areas, complicating effective conservation efforts and monitoring. This fragmentation hinders targeted protection and management strategies needed for population recovery. Therefore, stringent steps towards habitat restoration become the move forward especially for gharials who have specialised habitat requirements.

Lessons Learnt from Habitat Restoration

With the aim to specifically conserve the declining sloth bear species, a strategically planned initiative was taken up by Wildlife SOS to restore the wild habitat of Ramdurga Valley in Karnataka. The journey of this project was strongly supported by in-depth knowledge of the local land which was once known for its rich flora and fauna. By planting indigenous plants and engaging the community that resides closest to the vicinity, habitat restoration across 50 acres has resoundingly succeeded. Not only did this project bring back sloth bears, but it also resulted in the return of diverse wildlife, including leopards, langurs, wolves, wild boars, pangolins, jackals and several avians as well. Now, Ramdurga Valley has become a self-sustaining ecosystem that can be looked at as an example and foundation for future rewilding projects.

Basking at the brink of extinction, the conservation of gharials requires a nuanced understanding of the species’ dependence on their habitat and the threats to the same. While controlled repopulation efforts have been successful, the key to ensuring the long-term survival of this ancient species lies in restoring balance to the affected ecosystem. By focusing on these efforts, we can enable gharials to breed and repopulate naturally, without human intervention.

To stay informed about our ongoing conservation efforts and learn more about how you can contribute, subscribe to our newsletter.