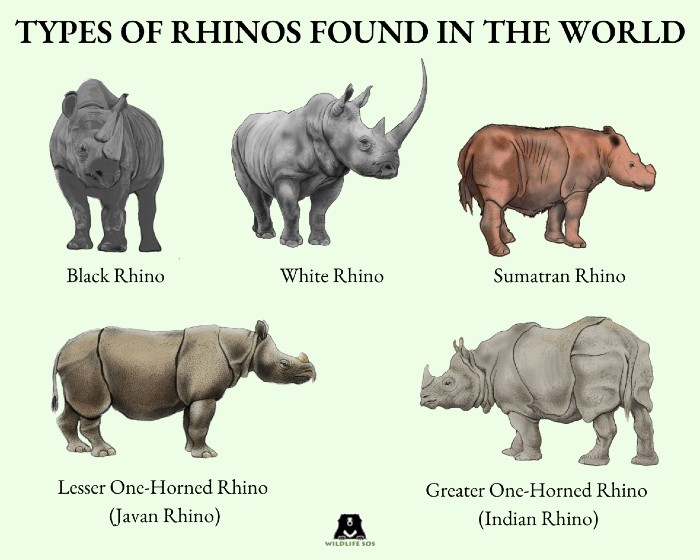

Rhinoceroses are one of the most fascinating and certainly one of the largest land animals to exist today. Despite that, many of us may not know how many rhinos actually roam the Earth, and where they are found. There are five species of rhinos that are found in only two continents – Asia and Africa. The continent of Asia is home to three rhino species, namely the Greater one-horned or the Indian rhino (Rhinoceros unicornis), the Lesser one-horned or Javan rhino (Rhinoceros sondaicus; also known as the Sunda rhino) and the Sumatran rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis). Africa, on the other hand, acts as a refuge for the African White rhino (Ceratotherium simum) and the African Black rhino (Diceros bicornis). Our quest is to know these threatened species better, so let us start with the rhinos who call the lands of Africa their home.

The Two Rhinos of Africa

The word ‘rhinoceros’ comes from the Greek word rhinokeros which translates to ‘nose-horned’ (rhinó, which stands for nose and ceros which means horn). It is interesting to note that except for the Indian and Javan rhinos, each of the remaining three rhino species belong to separate genera. The White rhino and Black rhino that are found in Africa belong to the Ceratotherium genus and Diceros genus respectively. The two species diverged from each other over 14 million years ago, however, their common names still remain misleading.

The African White rhino derives its name from the Afrikaans word wyd/weit, which translates to wide, and refers to the rhino’s broad, square-lipped mouth. It is believed that English naturalists misheard the Afrikaans word as ‘white’, leading to the rhinos’ misnomer. Both the White and the Black rhinos are actually grey in colour. African White rhinos are known to weigh over a whopping 3 tonnes (3,000 kg), which is more than the weight of two small cars!

There are two subspecies of the African White rhino which are recognised currently: the Southern White rhinoceros (C. s. simum) and the Northern White rhinoceros (C. s. cottoni). According to World Wildlife Fund (WWF), nearly 98.8% of the Southern White rhino population is found in four countries, namely South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Kenya. Out of all the species in the world, African White rhinos are the heaviest and roam the African savannas, sharing the habitat with other large mammals.

The African Black rhino, conversely, is smaller than the White rhino and its most notable physical feature is its hooked upper lip. While White rhinos are grazers who feed on low-lying grass, Black rhinos’ pointed lips assist them to feed on leaves from bushes and trees, making them browsers. Another variant feature of Black rhinos is that they are double-horned, which is why they carry the specific epithet bicornis in their scientific name. These double-horned ungulates are found in more diverse habitats than White rhinos such as desert and semi-desert regions, tropical grasslands, woodlands, forests and wetlands. To date, there are seven recognised subspecies of the African Black rhino, of which only three remain extant. These include the Eastern Black rhino (D. b. michaeli), the South Central black rhino (D. b. minor) and South-western black rhino (D. b. occidentalis).

The Three Rhinos of Asia

Now that we are well-versed with the rhinos of Africa, it is time to shift our focus to their Asian cousins. The three Asian rhinos, namely the Greater one-horned rhino (Indian rhino), the Javan (Lesser one-horned) rhino and the Sumatran rhino are restricted to south and south-east Asia, in the countries of Indonesia, Nepal and India, and in the island of Borneo.

Rhinoceros unicornis is the scientific name given to the Indian rhino, with uni meaning one, and cornis meaning horn in Latin. The Greater one-horned rhinoceros is the largest of the three rhino species found in Asia. It is found in the alluvial Terai-Duar grasslands and riverine forests at the foothills of the Himalayas spanning India and Nepal. In India, this species is concentrated mainly in the Brahmaputra valley of Assam, and in Nepal, the Terai grasslands. The Indian rhino, along with the African White rhino, share the crown of being the largest rhino species in the world. The Indian rhino is second only to the Asian elephant in terms of the largest animals in Asia! Despite being so heavy, they can run at speeds of up to 55 km/h. Given their weight and size, it is difficult to believe that they are grazers and their diet almost entirely consists of grass, and sometimes can include fruits, leaves from shrubs and trees, and aquatic plants.

The Javan rhino is a smaller version of the Indian rhino, and is also known as the Lesser one-horned rhino. They possess similar loose folds on their skin as Indian rhinos, which gives them an armour-plated appearance. Javan rhinos are currently found only in the tropical forests of Indonesia’s Java. Sumatran rhinos, on the other hand, are found in dense tropical and subtropical forests lying in the lowlands and highlands of Borneo and Sumatra. Sumatran rhinos are in fact the smallest species of rhinos, and the only ones in Asia with two horns.

Despite being separate species, there are certain commonalities between the three rhinos of Asia. They have poor vision but excellent olfactory senses, so much so that they sometimes communicate by smelling each other’s dung. Just like their African relatives, rhinos found in Asia are quite fond of mud, but additionally, they are excellent swimmers too. Talk about crossing rivers with ease! Lastly, it is essential to highlight that all three Asian rhinos are jeopardised by anthropogenic factors, like poaching, habitat loss and habitat fragmentation.

Rhinos in Peril

When we talk about threats, there are very few species on the planet that are as threatened as the rhinos. Three out of the five rhinos are categorised as ‘Critically Endangered’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Poaching and illegal wildlife trade is the biggest threat to rhinos across the globe. The illegal market in Vietnam and China for rhino horns, driven by frenzied consumer demand, has left African rhinos teetering on the brink of extinction. Like elephant ivory, rhino horns have also become a status symbol and a representation of affluence. The horns are also believed to cure cancer, act as a health supplement and even as a hangover cure!

According to WWF, “Rhino poaching levels hit record highs in 2015, with poachers slaughtering at least 1,300 rhinos in Africa. Six hundred and ninety one rhinos were poached in South Africa in 2017.” This situation echoes for the Indian rhino as well; reportedly, close to 100 rhinos were poached in India between 2013 and 2018 for their horns, which were to be used in traditional Chinese medicines.

In the case of Indian rhinos, increased severity of floods by the Brahmaputra river due to climate change, along with habitat degradation, encroachment and livestock overgrazing are some of the other threats they face today. Currently, out of the current global population of more than 3,700 Indian rhinos, over 2,700 individuals are found in India. The state of Assam tops the list with 2,613 rhinos, followed by West Bengal that last recorded 135 rhinos.

The Javan and the Sumatran rhinos, on the other hand, fight against enemies such as habitat loss and fragmentation. As a result, both species are left with dangerously low numbers – less than 70 Javan rhinos and less than 80 Sumatran rhinos left in the wild. Man has pushed these animals into such a tight corner that most of the historical home range of these two species is now gone. All over the world, a trend of confining animals within a certain region has been observed. To coexist with wildlife, there is no other way but to work with nature and provide better protection to wild habitats — the very source of all natural wealth. Now is when we need to protect both the species and the ecosystem.

For more interesting stories on nature and wildlife, subscribe to the Wildlife SOS newsletter!