In 1903 Thomas Edison made a 60-second film aptly titled “Electrocuting an Elephant.” The black and white film showcased the brutal electrocution of Topsy, an Asian elephant that could no longer be managed by her owners. Her entire life, Topsy was a circus elephant used as a mere prop for the entertainment of humans. Even in her death, Topsy was reduced to an object to be gawked at as she took her last breath. The film was watched by millions and continues to be in circulation today. Many gauge that Edison made the film to discredit a new form of electricity: alternating current. Yet, what the film ended up illuminating was the deep-rooted demand for the visual consumption of animals, specifically elephants.

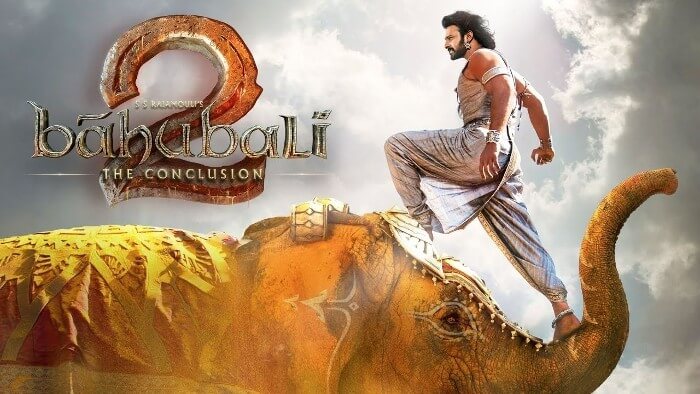

The desire to watch elephants adorn our screens has only increased since. While we may no longer be seeing the electrocution of an elephant, popular culture continues. Used in stunts or as whole characters for commercials and movies, elephants are a common sight on our screens. For example, the viral scene from the movie “Bahubali 2: The Conclusion” showcased actor Prabhas climbing an elephant. So appreciated was the scene that the trend took over social media in India with various mahouts climbing their elephants “Bahubali style.” The West couldn’t stop itself from being enamored by stunts involving elephants. Rene Cassley, Instagram’s “elephant boy,” has repeatedly gone viral for doing tricks with elephants, such as making an elephant shoot a basketball shot.

Human-animal interface pertaining to the domain of cinema and pop culture poses various questions for wildlife conservationists. The primary question is about the physical well-being of the animal being utilized to create content. Secondly, the larger ecologically damaging discourse created by treating animals as props. At their core, any wild animal does not belong in the entertainment industry to be trained and utilized for entertainment.

Before the start of every film, audiences are assured that “no animal was harmed in the making of this film.” In fact, numerous laws do exist worldwide that ensure no animal is abused while filming. The Supreme Court of India ruled that any film utilizing animals must get approval from the Animal Welfare Board of India (AWBI). An apex court in Mumbai upheld the judgment, declaring AWBI the authority to issue clearance certificates for any such films, TV shows, commercials, etc.

However, the reality of abuse endured by animals to be filmed is more nuanced than we might think. While abuse might not occur on the sets of a film, an elephant still undergoes brutal training and torture prior to filming. Like elephants are captive in the abusive tourism industry, elephants in the entertainment industry are also poached as calves. They are made to undergo a brutal process of initiation called “phajaan” where an elephant’s wild spirit is broken through repeated whips of a bullhook. Once willing to obey its master, an elephant is then taught to cease being wild and be obedient, perform tricks and henceforth be useful in filming.

Thus, while an elephant might not have been abused on a set itself, it has already undergone years of trauma to make it obedient. The brutal abuse borne by elephants to be trained was brought into the spotlight during the filming of “Water for Elephants” (2011). The film had an unusual actor Tai, an Asian Elephant. While the movie spoke about compassion for elephants, Animal Defenders International revealed footage of Tai the elephant being brutally abused while in training. While the allegations have been denied, it is no mystery that to film with an animal as magnanimous as the Asian elephant, it has to be tamed. Tai was captured from the wild and placed in captivity under the ownership of Gary and Kari Johnson; The two own Have Trunk Will Travel, an organization that provides elephant rides, shows, events, and commercial appearances. While the organization denies using abuse during the film, their decision to relocate to Texas after California banned the use of bullhooks, a tool used to discipline elephants, speaks volumes about the nature of their business.

Such practices also create demand for more elephants to be poached from the wild, fueling an already burgeoning trade in wild elephants. What makes the use of elephants for commercial television and pop culture even more horrific is the availability of a safer alternative – Computer Generated Imagery or CGI. The use of technology to represent animals can ensure that viewers learn more about the wild world without the abuse being inflicted on animals. Despite such a safe alternative, many filmmakers continue to exploit elephants for the purposes of accurate cinematic representation. Numerous filmmakers have also been caught claiming to use CGI while, in actuality, using live elephants.

Apart from the physical abuse inflicted on elephants for the purpose of filming, there also exists a larger and rather existential downside to this conundrum – how are we as a species learning about and relating to animals? An ethical, ecological framework posits all members of an ecosystem as equal and valued in their own right. Yet, by utilizing elephants as props for filming, we reduce them to mere objects, only valuable as long as they are of use to us. Such a framework does not encourage us to make a tangible change for animals but merely pays lip service to their rights. Rather than calling out to our higher ecological consciousness, these visual displays teach us that animals are exciting and engaging but only in circumstances where humans are in power.

A more significant ecological crisis stares back at us with every animal we gawk at on our screen. The Asian Elephant population has declined by an estimated 50 percent over the past 75 years. With only 20,000 to 40,000 Asian elephants left in the wild, it is time to reclaim the visual medium as a platform for awareness rather than abuse.

This Save The Elephant Day you can refuse to ride elephants being used in the tourism industry and help India’s elephants! Visit refusetoride.org to find out more.