If you find yourself in an unfamiliar area, you can simply approach a passerby or open up a map app to ask for directions. Despite the language barrier or cultural differences, there is always a chance that you can be guided to your destination. What do you do in a situation where humans cannot help you and Google maps fail to be of much use? What would you do if you had to track an elusive animal within a forest, with no kind passerby around nor any access to the internet, to guide you?

Since there is pre-existing research on wild animals and herds, we know that wild animals can certainly be tracked. However, one cannot simply venture into the territory of a wild animal and expect to know the forest better than it does. How then, does one track the animal? If you suggest radio collars, we’d say you’re right.

Radio collars are a vital tool to study wildlife and provide us with immense data for our research, but someone has to track the animal first in order to radio-collar it! How is it that the concerned animal is found, so that scientists, researchers and conservationists can begin to follow its tracks?

The veterinary and research team at Wildlife SOS has some insights into this. As part of their elephant radio-collaring project in Chhattisgarh in 2018, the team tracked an elephant herd led by their matriarch, Van Devi. This particular herd would often enter human habitats and destroy crops. With the help of various photographs taken by the locals and the anecdotes mentioned by them, the team was able to identify which particular herd was causing the ruckus, so that they could chart out its movement. To do this, they ventured into forests to identify tracks left by elephants. Once the elephant herd was spotted, the team had to also follow the herd discreetly with their keen eyesight, sense of smell and hearing.

Elephants are gigantic animals, and when they pass through forests, they trample over various foliage. These elephants are not called “ecosystem engineers” without reason; they change entire landscapes in their wake! It was key for the team to watch out for marks alongside the trees where these giants may have scratched themselves, or broken branches with their powerful trunks.

Other than the flattened shrubs, these herds also leave their footprints on the forest floor. Judging from the condition of the footprint, one can analyse the time around which the herd was in the area. For example, in an area where the herd passed by a few moments ago, the footprints would have no grass or leaves covering them. If the mud is wet, the footprint would be very clear and deep. However, if some time has passed since the herd was in the area, the footprint may have dried up or may have been covered by fallen leaves.

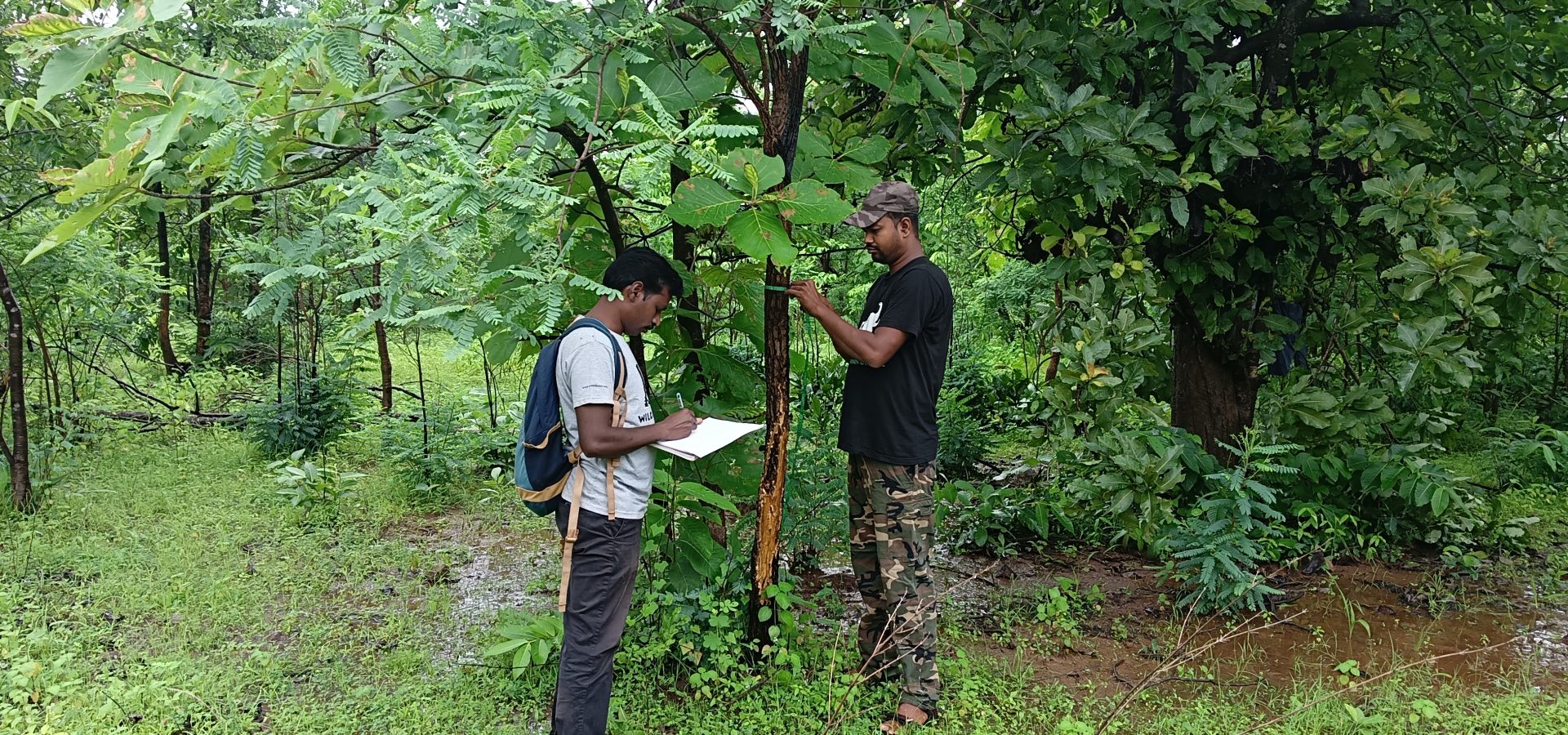

![Researchers at Jammu & Kashmir track Brown bears as a part of their study. [Photo (c) Wildlife SOS]](https://wildlifesos.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/brown-bear-project-3.jpg)

To track specific wildlife, it is essential to think like the animal and take into account its eating habits, food and water requirements and shelters. This can help understand where they can be found. By examining the plants consumed and by taking into account the angle at which they were chewed, experts can even tell whether the feeder was a rodent, cattle, or a sharp-toothed predator. Some other signs that one must keep an eye out for are oval depressions in the foliage, where animals might have made their beds, and scratches on the bark of trees where animals used their horns or claws to mark their territory.

The Wildlife SOS team looked out for significant cues such as fresh elephant faeces, watering holes, and foliage that elephants usually feast on. When the team reached closer to the elephants, they made sure to keep an ear out for sounds of trumpeting, footsteps, and even ear flapping which could help them find out the exact location of the animals. Once the matriarch was identified, it became crucial to separate her from the rest of the herd. This proved to be a tricky process since the herd follows its matriarch everywhere! Many opportunities were missed where the team could tranquillise the wild elephant before putting the radio collar on her. However, after multiple attempts, the team managed to isolate Van Devi about a kilometre away from her herd, and swiftly radio-collar her.

![The Wildlife SOS team successfully radio-collars Vann Devi. [Photo (c) Wildlife SOS/Lenu Kannan]](https://wildlifesos.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/radiocollar-CG.png)

Immobilising an animal requires caution and professional expertise since a wrong dosage can pose a great threat to both the humans and the animal involved. If an animal is poorly tranquilised, it could attack the surrounding humans in defence out of fear. If the dosage is too high, it could threaten the animal’s life. On the field, it is difficult to ascertain the animal’s medical history such as nutrition, pregnancy, disease and infection, which play a crucial role while tranquilising the animal.

When experts venture out into forests, they ensure that their presence is as unassuming as possible. This means wearing muted and earthy-coloured clothing to blend in with the surroundings easily. Perfumes or personal care products with unnatural fragrances must never be used, as these alert animals of a foreign presence. The more one smells like the forest, the better it is.

It is important to also be alert of kill sites, as those indicate that a predator was present in the area. However, unlike marks left on vegetation, kill sites are not as easy to analyse. This is because, at a large kill site, many other scavengers might have consumed parts of the prey as well. Hence, one might find many scat samples, scratch marks and tracks near a kill site. Researchers also analyse bones found along different paths to discern the species that was hunted.

![Conservationists often use camera traps to track and study wild animals. [Photo (c) Wildlife SOS]](https://wildlifesos.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/A-male-sloth-bear-seen-pede-makring-on-camera-trap-footage.jpg)

To track wild animals, experts often rely on the experience and ancestral knowledge of the tribes that live in and around the area of study. The Irula tribe of Tamil Nadu, for instance, are ace snake catchers who are familiar with the most venomous snakes. Originally forest dwellers, members of this tribe used to make their livelihood by culling snakes and selling their skins. Once this practice was stopped, many of them migrated to urban areas and were entrapped in the bonded labour system. Once the Irula Cooperative was formed, the tribe began to catch the ‘Big Four’ venomous snakes (Russell’s viper, Saw-scaled viper, Spectacled cobra and Common krait) to ethically extract venom which could create anti-venom. This way, they became vital to the medical industry. With their skill in tracking snakes, the tribal people would catch the snakes for venom extraction and release the snakes unharmed, making sure to mark the snakes so that they are not caught again till they recuperate from the venom extraction.

![Representational image of a Saw-scaled viper, one of the Big 4 venomous snakes in India. [Photo (c) Wildlife SOS]](https://wildlifesos.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Saw-scaled-viper-wsos.jpg)

With aid from the local communities, researchers are able to successfully locate wild animals so that they can radio-collar and study them remotely. The team at Wildlife SOS has also effectively fitted radio transmitters atop the the carapace (hard upper sheet) of Indian Star tortoises and ensured that that they were released safely into their natural habitat. This venture has allowed the team to study vegetation data, feeding trails, activity patterns and mating behaviour of this ‘Vulnerable’ tortoise species that are being illegally trafficked. Such studies prove to be invaluable to the conservation efforts of wild animals in India.

To save wildlife, do support our research projects by making a donation towards providing the research team with better equipment and better opportunities!