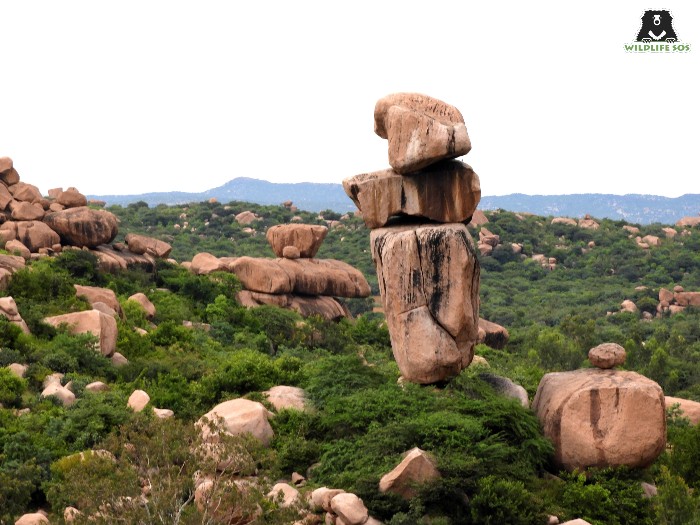

Picture this: a vast, barren land tarnished by the scars of exploitation — quarries echoing with the sound of mining, once-green vegetation reduced to stumps, and the silence of a vanishing ecosystem. Stretching for kilometres, the land has been stripped bare by unbridled anthropogenic forces of encroachment, illegal hunting, forest fires, and deforestation. This has led to diminished rainfall, leaving streams dry and the underground water table depleted. Not only does it impact the animals, but it exacerbates conflicts between them and villagers as well. This was the story of Ramdurga, an area nestled in Koppal, Karnataka.

In the same state, a few hundred kilometres away, Wildlife SOS had been managing the Bannerghatta Bear Rescue Centre to rehabilitate sloth bears, rescued from the ‘dancing’ bear practice. Curious to learn more about the mystery that Ramdurga was, our team members ventured into the landscape. Noticing remnants of wildlife indicated that a large community of animals was once flourishing here. Their numbers, however, had diminished due to the rampant degradation of the landscape. The group also came across scats of sloth bears and leopards near the rocky caves — a glimmer of hope on devastated land. Recognising the critical value of this unique habitat, the team took over the responsibility of rejuvenating and preserving it.

In 2006, Wildlife SOS pioneered a project aimed at the conservation of natural habitat in the Ramdurga Valley, which is not too far from Hampi. By purchasing 40 acres of the barren land, the organisation initiated the Ramdurga Habitat Restoration Project to reinstate balance in nature. It would not only create a sound habitat for wild animals, but act as a wildlife corridor too, connecting neighbouring habitats. This set the stage for a comprehensive conservation effort that would soon transform the valley into a rich forest.

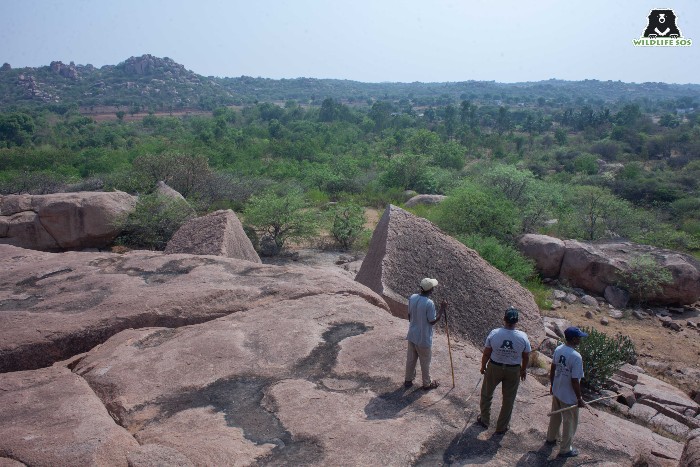

The Wildlife SOS took a community-centric approach by involving people living close to Ramdurga. By allocating the responsibility of managing the area, local members became the guardians of the land. Among them, six vigilant guards were appointed to patrol and survey the 40-acre habitat, which curbed human-induced activities such as forest fires, stone quarries, hunting, wood cutting, and encroachment. Regular awareness programmes were conducted in education institutes and in collaboration with village leaders to foster an understanding of the project and gain valuable support.

Having received a successful response, the team expanded its conservation initiatives by purchasing an additional 10 acres of land nearly six years later, with the support of BHEL and PSSR Chennai. This new land bordered a protected forest reserve, and would act as a bio-corridor that linked the area with a nearby lake.

The turning point to this effort came with the plantation of native trees and shrubs on the land. Horticulture experts were consulted, and the most appropriate species were selected. A team of guards worked round the clock to meticulously plant over 10,000 carefully chosen saplings across the restoration area. Mahua or butter tree, neem (Indian lilac), arjuna, mango, amla (Indian gooseberry), Indian beech, bamboo, custard apple, Indian laburnum, bodhi (sacred fig), banyan, and jamun (java plum), were among the many species planted. The nursery also has palm, teakwood, lemon tree, tamarind, and sapota trees.

By sowing these, the team breathed life back into the area’s soil, prompting a resurgence of wildlife. Soon, the desolate landscape underwent a remarkable metamorphosis, transforming into a vibrant refuge for animals. In a period of merely two to three years, the project achieved a plant survival rate of 90%, showcasing the resilience of nature when given the chance to rebound. The saplings, once scanty footnotes in the vastness, now stood tall — their girth expanding, and their branches reaching for the sky. Where arid hills stood, lush green forests emerged once again, providing sanctuary for a multitude of species.

The revival of Ramdurga Valley was key in bringing back the lost biodiversity. After helping it take its first steps, the self-sustaining habitat now has abundant birds, mammals, and reptiles that are being recorded. Leopards, tortoises, wolves, jackals, wild boars, langurs, and pangolins have found solace in the restored habitat. Sloth bears, the flagship species of the Ramdurga Valley, also made a comeback, and can now be seen using the area as a habitat corridor. Indian star tortoises, known for their radiating patterned carapace, are seen laying eggs here by digging into the soil. Other reptiles spotted include monitor lizards, chameleons, and snakes. The endemic yellow-throated bulbul, once exclusive to the Deccan Peninsula in South India, has also successfully returned to this region. Small mammals such as jungle cats, small Indian civets, Asian palm civets, and species of mongoose also call the regenerated land their home.

The underground water table replenished, which brought relief to wildlife, the flora around them, and the local farmers as well. Once dry, the streams had begun to flow for over nine months a year! Additionally, a generous move was made for the animals by Water For Voiceless, an animal rights group, that contributed supplies like water troughs, which were installed throughout the area so that they could be filled with water in the summer months.

The scarcity of water in Ramdurga had also deeply affected the two predominant human communities residing here — Valmikis and Banjaras. Their members were forced to migrate due to shortage, particularly in the summer months. It was during this period that ritual hunting practices took place at a larger scale. A community-centric approach was therefore taken to develop an irrigation system that would support the needs of the locals. While the hunting activities were monitored by the patrolling guards, Wildlife SOS established vital structures to create effective irrigation that also gave rise to native wetlands. A bore well, drip irrigation system and solar-powered electrical fencing were put in place for accessibility to water and the protection of land. The positive impact was swift and profound; fewer people migrated, and agricultural activities began to thrive all year round.

Having accomplished these milestones did not stop Wildlife SOS researchers from learning more about the habitat and wildlife. In 2014, they furthered their commitment to wildlife conservation by initiating a research project in several divisions of Karnataka, including Ramdurga. The study was led by biologists and veterinarians from Wildlife SOS, in collaboration with Bear TAG and Hogle Zoo from the USA, to understand the behaviour, ecology, and denning patterns of wild sloth bears. Taking long hikes through the landscape, with gusts of hot, dry wind swirling the dust around, the team managed to observe direct signs (such as sighting of animals), as well as indirect signs (scratch marks on trees, pugmarks, or scats). Researchers have been closely monitoring bear activities, mapping their behaviour, and collecting scientific data. Through extensive field investigation and community education, the team continues to mitigate human-bear conflicts and protect the natural habitat of these vulnerable animals.

The story of Ramdurga is not just a tale of habitat restoration, it is an attestation to the power of conservation and community engagement. As the project continues to make strides, Wildlife SOS calls upon you to make a meaningful impact in safeguarding these invaluable habitats and the species that call them home. You can help us sustain our efforts by donating here.